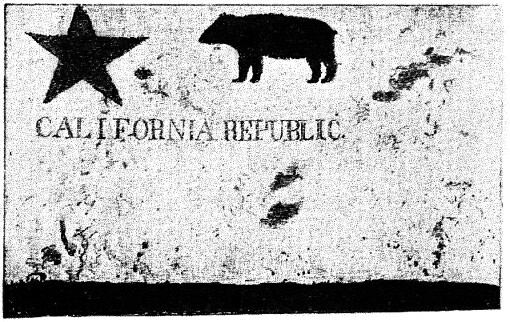

Historic California Bear Flag as photographed in 1890.

This flag, raised at Sonoma on June 14, 1846, was the first day of the California Republic, which lasted until July 9, 1846.

June 14, 2018 - As American settlers moved into Mexican-controlled California, most groups settled either in the Sonoma-Napa area, or north of Sutter's Fort near present day Sacramento. A very few of them obtained grants of land from the Mexican authorities, which put the legality of the settlers' claims to land into question. In April of 1846, Mexican Governor Jose Castro proclaimed that the purchase or acquisition of land by foreigners who had not been naturalized as Mexicans "will be null and void, and they will be subject (if they do not retire involuntary from the country) to be expelled whenever the country might find it convenient."2

Rumors began to spread that Castro's edict would soon be enforced, and that Native Americans had been encouraged to burn the crops of the foreigners. Several leaders of the settlers discussed their concerns of Mexican aggression with U.S. Army Captain John C. Fremont at a meeting, in which Fremont failed to promise assistance, but encouraged the settlers to resist.1

Early in June, Mexican General Mariano Vallejo, commandant of the northern frontier at Sonoma offered 170 horses to Castro, who was then organized at Santa Clara. Once the settlers heard those horses were to be used to uproot their claims, they began to mobilize an armed force to stop the transfer. The small force came under the leadership of Ezekiel "Stuttering Zeke" Merritt, an old Rocky Mountain trapper, who seemed to have harbored an overpowering resentment against Vallejo, who allegedly struck Merritt previously.1 "Merritt was a brawny, stern man of forty years age; he is hard featured, has bloodshot eyes and a peculiar stuttering speech. His whole appearance and manner was that of a man moved by some revengeful intoxicating passion."3

On the morning of June 9th, a party of about ten men set out to capture the horses and prevent them from reaching Castro's forces in Santa Clara. Merritt's men accomplished their mission, and they brought their newly acquired horses to Fremont's camp. Soon after arriving at the camp, the small force (now 20 men strong) left to launch an assault on the town of Sonoma. The town was not garrisoned, but it was home to the very influential General Vallejo. By capturing Sonoma, the rebels sought to protect the American settlers in the area. On June 14th, Merritt's force entered the town of Sonoma. The surprise was complete. Vallejo was awakened and made prisoner. The prisoners were then transported to Sutter's Fort in Sacramento.1

Of course, it was necessary to design a flag to replace that of Mexico. The central feature of the flag became a grizzly bear. The bear designed on the flag was the source of much entertainment, due to its closer resemblance to a hog. The original flag was eventually destroyed in the San Francisco fire in 1906. Because of their flag, the insurgents immediately became known as the Bears and their uprising became known as the Bear Flag Revolt.1

Given the lightly fortified garrison of settlers at Sonoma, and the threat of an assault on the town by Castro in the immediate future, Captain Fremont threw off any pretense of neutrality and left for Sonoma on June 24th. In addition to his forces, many new settlers joined, bringing the force at Sonoma to about 90 men.1

In late June of 1846, Fremont advanced to San Solito, present day Sausalito, and launched and assault on the undefended Castillo de San Joaquin, on the south side of the Bay entrance. The seven cannon stationed at the Castillo were spiked to prevent them from being used. Fremont also dispatched a small contingent to patrol the narrows of the Bay, preventing any communication or passage of Mexican forces.1

The Bears, largely by their actions at Sonoma, had gained considerable control north of San Francisco Bay. When Fremont joined the revolt in Sonoma, their control over the area was assured.1 The Bear Flag Revolt put the territory claims of Mexico into question, paving the way for the United States to seize control of the Pacific Coast shortly thereafter.

1. Rogers, Fred B. Montgomery and the Portsmouth. John Howell-Books, 1958.

2. Ford's MS. The Bear Flag Revolt. Bancroft Library aquisition.

3. Duvall, Marius. A Navy Surgeon in California, 1846-1847. San Francisco: John Howell

Source: NPS

California pioneer John Bidwell chronicled many of the events surrounding the “Bear Flag Revolt,” and wrote, in 1890:

“Among the men who remained to hold Sonoma was William B. Ide, who assumed to be in command. In some way (perhaps through an unsatisfactory interview with Frémont which he had before the move on Sonoma), Ide got the notion that Frémont's hand in these events was uncertain, and that Americans ought to strike for an independent republic. To this end nearly every day he wrote something in the form of a proclamation and posted it on the old Mexican flagstaff. Another man left at Sonoma was William L. Todd who painted, on a piece of brown cotton, a yard and a half or so in length, with old red or brown paint that he happened to find, what he intended to be a representation of a grizzly bear. This was raised to the top of the staff, some seventy feet from the ground. Native Californians looking up at it were heard to say ‘Coche,’ the common name among them for pig or shoat. More than thirty years afterwards I chanced to meet Todd on the train coming up the Sacramento Valley. He had not greatly changed, but appeared considerably broken in health. He informed me that Mrs. Lincoln was his own aunt, and that he had been brought up in the family of Abraham Lincoln.”

The Bear flag was in the possession of the Society of California Pioneers at the time of the 1906 Great Earthquake and Fire, and burned during the conflagration.

According to the California Blue Book:

“The flag was designed by William Todd on a piece of new unbleached cotton. The star imitated the lone star of Texas. A grizzly bear represented the many bears seen in the state. The word, ‘California Republic’ was placed beneath the star and bear. The Bear Flag was replaced by the American flag. It was adopted by the 1911 State Legislature as the State Flag. ”

Source: The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

For more information on the Bear Flag Revolt: Wikipedia